-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Emergency evacuation low-pressure suction for the management of extravasation injuries – a case report

Authors: Van Look L 1; Vissers G. 1,2; Tondu T. 1,2; Thiessen F. 1,2

Authors place of work: Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Antwerp University, Wilrijk, Belgium 1; Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, University Hospital Antwerp, Edegem, Belgium 2

Published in the journal: ACTA CHIRURGIAE PLASTICAE, 64, 1, 2022, pp. 44-49

doi: https://doi.org/10.48095/ccachp202244Introduction

Extravasation is the movement of fluid outside its conduit (e.g. vein, intravenous line, or portal catheter) to the extracellular tissue environment, possibly leading to a local inflammatory reaction, compartment syndrome, tissue necrosis, and full thickness skin loss at the affected area [1]. All ages are susceptible, but especially the neonates and elderly people, in whom the skin and subcutaneous tissues are thin and poorly supported, are at risk [2]. The most common sites for extravasation injuries are at the dorsum of the hand, the forearm, the antecubital fossa, and the dorsum of the foot [2]. The overall incidence of extravasation injuries in adults is considered to be between 0.1–6% of intravenous therapies [3]. Incidences are higher in patients receiving chemotherapy: in adults (4.7–6.5%) and in children (11–58%) [1,4]. However, the number of extravasations involving potentially harmful agents is small [4]. Extravasation at the level of a central catheter is rare, accidental extravasations have been reported in 0.3–4.7% of cases [5]. This can be explained by the routinely implemented radiographic confirmation of catheter position in central administration techniques [6]. Hartkamp et al experienced two cases with extravasation in their series of 126 patients [7]. Boussen et al reported one case of extravasation in 205 implanted central catheter ports [8]. If extravasation occurs at the level of a portal catheter, it usually happens by one of four mechanisms: incomplete needle placement and needle dislodgement, thrombus or fibrin sheath formation, perforation of the superior vena cava, and catheter fracture [9]. Drugs are classified as irritant, vesicant and non-vesicant based on their potential for local toxicity [3,10]. An irritant can cause an inflammatory reaction characterised by swelling, warmth, erythema, and tenderness but has no directly tissue-damaging effects [10]. Vesicants, such as cytostatics, have the potential to cause blistering, sloughing of the skin, and varying degrees of deep tissue damage because they are inherently toxic [10]. Non-vesicant drugs rarely produce acute reactions or tissue necrosis [3]. In areas with little subcutaneous fat (e.g. dorsum of the hand, dorsum of the foot, or antecubital fossa), vesicants may also cause severe damage to the underlying nerves, tendons and joints [4]. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is a complex mixture of substances including amino acids, dextrose, lipids, vitamins, electrolytes and trace elements [11]. Tissue toxicity of TPN could be related to the hyperosmolality, acidic pH and local ions present in TPN [11]. Overall tissue damage results from a combination of several factors, including volume, concentration, osmolality, inherent cytotoxicity, and vasoconstrictive properties of the drug, as well as contact time, infusion pressure, and regional anatomical peculiarities [1,2,10,12]. The treatment of complications may entail debridement and – depending on severity – skin grafting or flap coverage. However, if recognised and treated early, complications could be avoided and conservative or less invasive treatment techniques such as saline wash-out or aspiration may be used.

Case description

A 54-year-old Caucasian woman presented to the emergency department with an extravasation injury into the right breast following a TPN leakage from her port catheter inserted at the right cephalic vein. The patient received TPN in the context of Crohn’s disease, and was administered by community nurses on a daily base. The patient also had a previous lumpectomy in the left breast. The patient presented at the emergency department with an inflammatory swelling of the right breast and a little less than 24 hours following her last TPN administration. A mispuncturing of the port catheter was suspected with an overnight leakage of 1.5 litres of TPN into the breast. There was a breast asymmetry with an approximate threefold increase of the right breast volume accompanied by diffuse erythema (Fig. 1). The skin was intact, and no well-defined collection could be palpated. The patient was systemically well. Radiographic examination confirmed the correct position of the portal catheter.

Fig. 1. Clinical presentation. Clinical presentation featuring breast asymmetry and erythema of the diffusely swollen right breast, but no skin necrosis. No well-defined collection could be palpated, contraindicating incision and drainage. The scar of a previous lumpectomy can be noticed on the left breast.

Because no palpable collection could be located, the decision was made to perform an aspiration of the extravasated fluid in the diffusely swollen breast (Fig. 2). Neither infiltration nor wash-out procedure was performed. Two small stab incisions were made: one at the medial side and one at the lateral side of the inframammary fold, followed by spontaneous drainage of approx. 200 mL TPN. A multihole cannula was used to perform a dry aspiration of the tense and swollen areas of the right breast. The suction strength was put on low-pressure in order to minimise unwanted healthy fat tissue evacuation. Aspiration was stopped when healthy fat tissue appeared in the tube. With this dry aspiration, 340 mL of the extravasated fluid was evacuated (Fig. 3). The stab incisions were closed with interrupted polyglactin 910 sutures and a light dressing was applied. On the first postoperative day, the patient was in better condition and experienced less discomfort. The right breast was suppler, and the dressings were clean and dry. The patient was discharged with oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid tablets for one week. Two weeks postoperatively, the patient was reviewed in the outpatient clinic with no further complaints and a soft and normalised volume of the right breast (Fig. 4). A subtle remaining asymmetry of the breasts can be seen because of the previous lumpectomy to the left breast.

Fig. 2. Dry emergency evacuation low-pressure suction of the right breast. Intraoperative photo of the dry emergency evacuation low-pressure suction that was performed. Two small stab incisions were made: one at the medial edge and one at the lateral edge of the inframammary fold.

Fig. 3. The collection canister. Intraoperative photo of the collection canister. In addition to a spontaneous evacuation of 200 mL, the canister contained about 340 mL at the end of the dry emergency evacuation low-pressure suction. No healthy fat tissue was evacuated.

Fig. 4. The outcome following emergency evacuation low-pressure suction. Clinical photos two weeks postoperatively demonstrate a normalisation of the right breast volume. The breast is soft and non-tender on clinical examination. A subtle remaining asymmetry of the breasts can be seen because of the previous lumpectomy to the left breast.

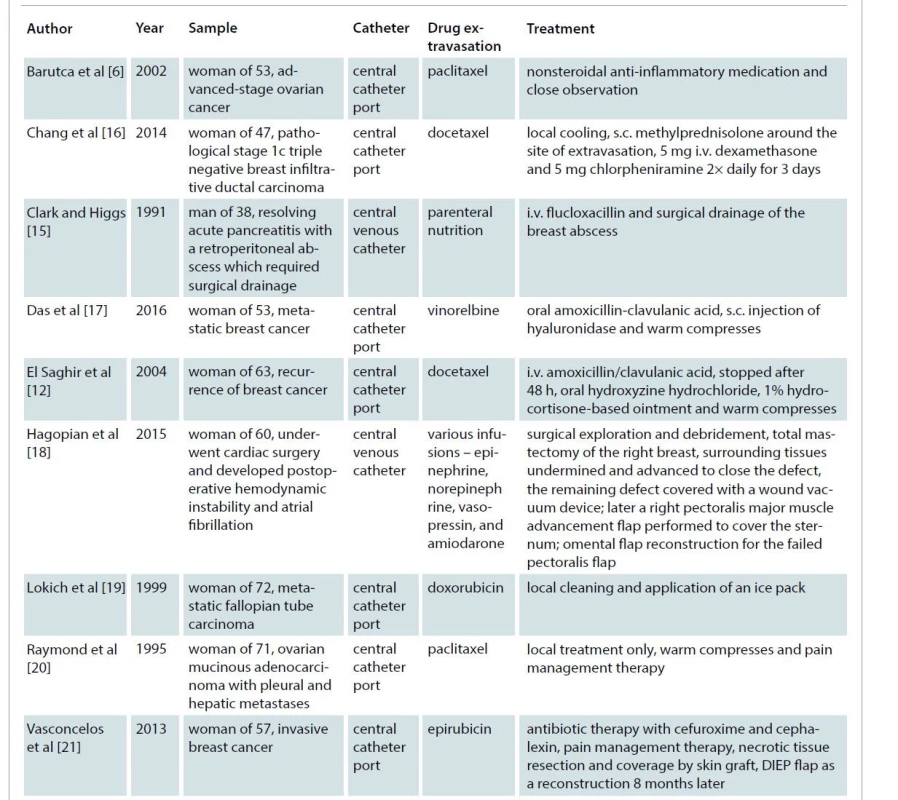

Only a few cases of extravasation injuries into the breast have been described (Tab. 1). Most cases are chemotherapy extravasations related to breast cancer treatment. The majority of research on extravasation injuries examines the treatment of these extravasated cytostatic agents [11]. Conservative treatment, topical nitroglycerin, hyaluronidase administration, saline wash-out, aspiration and drainage are options described for the early treatment of extravasation injuries [2,4,13] and can be used in extravasation injuries at the level of the breast. Untreated, these injuries can lead to skin and soft tissue necrosis demanding important reconstructive procedures with debridement and flap coverage.

Tab. 1. Selected case studies of extravasation injuries at the level of the breast.

DIEP – deep inferior epigastric perforator, i.v. – intravenous, s.c. – subcutaneous Discussion

The first step in managing an extravasation injury includes early recognition and referral, immediate discontinuation of the infusion and leaving the cannula in situ as it may be used as a route to aspirate the extravasated drug or to dilute with a normal saline infiltration and to administer an antidote. Conservative measures consist of watchful waiting, marking the affected area, elevation of the affected limb and application of heat or cold compresses. Davidoss et al reported a case of parenteral nutrition extravasation in the neck managed with conservative measures only, resulting in a full recovery without any complications [11]. Topical nitroglycerine has a vasodilating effect to counteract the intense local vasoconstriction caused by the extravasation and may prevent ischemia and skin necrosis [13]. However, caution must be taken, because nitroglycerine can cause systemic cardiac adverse effects and therefore is not recommended in practise [13]. Subcutaneous hyaluronidase can be administered to depolymerise hyaluronic acid, thereby making the connective tissue more permeable [4,13]. A hyaluronidase injection at the edges of the extravasation site allows rapid diffusion of the extravasated drug over a larger area, and therefore a sufficient dilution and absorption from the tissue, minimising the injury [13]. Additionally, it enhances the wash-out of the extravasated drug by reducing interstitial tissue viscosity. Topical hyaluronidase is also effective in reducing skin necrosis, in a rabbit model, if commenced within one hour of the injury [2]. Gil et al used chondroitinsulfatase with very similar actions to those of hyaluronidase, and obtained satisfactory results for treatment of TPN extravasation injuries [13]. The use of subcutaneously administered hyaluronidase has been advocated for parenteral nutrition extravasation; however, its use is currently only recommended for the extravasation of plant alkaloids [11].

In saline wash-out, small exit stab incisions are made around the periphery of the area of extravasation, and a large volume of normal saline is flushed through the subcutaneous space to wash it out [2,4,]. Although Gault et al described the insertion of a Veress needle [4], the authors prefer to leave the original catheter, that was used for venous access in situ as this guarantees wash-out at the exact location of the extravasation. Gault used his technique in the neonatal intensive care setting to treat two new-borns with TPN extravasation. Haslik et al promoted the use of this technique for early detected port catheter extravasations of vesicant drugs [5]. If the referral was made within 48 h of extravasation, they explanted the portal catheter and performed a subcutaneous wash out procedure [5]. Similarly to the technique described by Gault et al, they made several stab incisions to allow sufficient rinsing of the affected area. Additionally, they closed the incisions without tension and a redon drain was placed in the former port site to collect the residual fluid in the following days [5]. Vandeweyer and Deraemaecker promoted the efficiency of early suction and saline washout of extravasated cytotoxic drugs [14]. The area of extravasation was first suctioned and subsequently washed out with saline to be aspirated again using a liposuction device [14]. In case of a palpable subcutaneous collection or abscess, surgical incision and drainage is indicated. Clark and Higgs reported a breast abscess following extravasation of TPN via a central venous catheter [15]. Despite their early introduction of the appropriate antibiotic treatment on clinical suspicion of a staphylococcal infection, a breast abscess developed, necessitating surgical drainage [15]. Liposuction, described by Gault et al, is another treatment modality for extravasation injuries [4]. Although the technique is similar, liposuction is not the right term as there is no intention to evacuate healthy fat tissue, and this might be confusing for other medical staff and patients. We would like to suggest a new and more appropriate term – EELS, which describes better the situation. The term EELS might help emergency doctors, general surgeons, non-surgical specialities, and patients to better understand the treatment as it will break the affiliation with an aesthetic procedure. EELS can be performed under either local or general anaesthesia, depending on the location and extent of the injury. EELS was performed in an urgent setting (less than 24 hours after the injury) to avoid extensive tissue necrosis and abscess formation as described in other cases of TPN extravasation [15]. We had a spontaneous evacuation of 200 mL after making two small stab incisions. Ideally, EELS is used for diffusely spread extravasation injuries. It allows the surgeon to aspirate the extravasate before it can cause further damage. Care must be taken to minimise the aspiration of healthy subcutaneous fat, as this will leave the patient with disfiguring contour deformities. Therefore, in EELS the suction pressure should be low to minimise unwanted healthy fat tissue evacuation, hence the new term. In this case, EELS was performed via two minor incisions at inconspicuous places, to optimise aesthetic outcome. During the procedure, an estimate of the residual swelling in the affected breast, caused by the inflammatory reaction and hyperosmolality of the TPN, must be made to correctly predict the final breast volume to ensure breast symmetry. But in general, the endpoint of the aspiration should be the appearance of healthy fat into the tube. Dry suction eases this estimation because it is not biased by infiltration fluid volume, and allows more precise differentiation of healthy fat as tumescent aspiration liquifies the fat aspirate. We performed dry EELS and obtained a satisfactory result with full evacuation of the non-cellular extravasation fluid. However, it is important to mention that in vesicant extravasation injuries, the area should be diluted with normal saline infiltration [3]. If in doubt of a full retrieval of the extravasation fluid, a secondary lavage with saline wash out, as described by Vandeweyer and Deraemaecker, is a valuable option [14]. In our case, a rapid recovery was seen with an almost immediate decrease in discomfort, and an aesthetically pleasing outcome.

Conclusion

Extravasation injuries require adequate and prompt management to avoid late sequalae such as soft tissue damage and subsequent breast scarring and malformation. This case report describes how dry aspiration can be applied in the management of early TPN extravasation injuries at the level of the breast. Although the technique is similar, liposuction is not the right term for the emergency treatment of extravasation injuries. EELS describes better the situation as no healthy fat tissue should be evacuated during this procedure and might help medical staff and patients to better understand the treatment as it will break the affiliation with an aesthetic procedure.

Disclosure of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The authors declare that this study has received no financial support. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Author contributions: Lawrence Van Look: conceptualisation, study design, review of the literature and writing original draft; Gino Vissers: supervision, review and editing; Thierry Tondu: supervision, review and editing; Filip Thiessen: supervision, review and editing.

Lawrence Van Look

Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences,

Antwerp University

Universiteitsplein 1

2610 Wilrijk (Antwerp)

Belgium

e-mail: lawrence.vanlook@student.uantwerpen.be

Submitted: 28. 11. 2021

Accepted: 30. 1. 2022

Zdroje

1. Alexander L. Extravasation injuries: a trivial injury often overlooked with disastrous consequences. World J Plast Surg. 2020, 9(3): 326–330.

2. Kumar RJ., Pegg SP., Kimble RM. Management of extravasation injuries. ANZ J Surg. 2001, 71(5): 285–289.

3. Doornaert M., Monstrey S., Roche N. Extravasation injuries: current medical and surgical treatment. Acta Chir Belg. 2013, 113(1): 1–7.

4. Gault DT. Extravasation injuries. Br J Plast Surg. 1993, 46(2): 91–96.

5. Haslik W., Hacker S., Felberbauer FX., et al. Port-a-cath extravasation of vesicant cytotoxics: surgical options for a rare complication of cancer chemotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015, 41(3): 378–385.

6. Barutca S., Kadikoylu G., Bolaman Z., et al. Extravasation of paclitaxel into breast tissue from central catheter port. Support Care Cancer. 2002, 10(7): 563–565.

7. Hartkamp A., van Boxtel AJ., Zonnenberg BA., et al. Totally implantable venous access devices: evaluation of complications and a prospective comparative study of two different port systems. Neth J Med. 2000, 57(6): 215–523.

8. Boussen H., Mtaallah M., Dhiab T., et al. Evaluation of implantable sites in medical oncology in Tunisia. Prospective study of 205 cases. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2001, 20(6): 509–513.

9. Schulmeister L., Camp-Sorrell D. Chemotherapy extravasation from implanted ports. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2000, 27(3): 531–538.

10. Park HJ., Kim KH., Lee HJ., et al. Compartment syndrome due to extravasation of peripheral parenteral nutrition: extravasation injury of parenteral nutrition. Korean J Pediatr. 2015, 58(11): 454–458.

11. Davidoss NH., Ha JF. Extravasation of parenteral nutrition in the neck: a case report. Gen Int Med Clin Innov. 2017, 2(3): 1–3.

12. El Saghir NS., Otrock ZK. Docetaxel extravasation into the normal breast during breast cancer treatment. Anticancer Drugs. 2004, 15(4): 401–404.

13. Gil ME., Mateu J. Treatment of extravasation from parenteral nutrition solution. Ann Pharmacother. 1998, 32(1): 51–55.

14. Vandeweyer E., Deraemaecker R. Early surgical suction and washout for treatment of cytotoxic drug extravasations. Acta Chir Belg. 2000, 100(1): 37–38.

15. Clark KR., Higgs MJ. Breast abscess following central venous catheterization. Intensive Care Med. 1991, 17(2): 123–124.

16. Chang PH., Wang MT., Chen YH., et al. Docetaxel extravasation results in significantly delayed and relapsed skin injury: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2014, 7(5): 1497–1498.

17. Das CK., Gogia A. Vinorelbine-induced chemotherapy port extravasation. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17(12): e568.

18. Hagopian TM., Ghareeb PA., Arslanian BH., et al. Breast necrosis secondary to vasopressor extravasation: management using indocyanine green angiography and omental flap closure. Breast J. 2015, 21(2): 185–188.

19. Lokich J. Doxil extravasation injury: a case report. Ann Oncol. 1999, 10(6): 735–736.

20. Raymond E., Cartier S., Canuel C., et al. Extravasation of paclitaxel (Taxol). Rev Med Interne. 1995, 16(2): 141–142.

21. Vasconcelos I., Schoenegg W. Massive breast necrosis after extravasation of a full anthracycline cycle. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, 2013: bcr2013201179.

Štítky

Chirurgia plastická Ortopédia Popáleninová medicína Traumatológia

Článek Editorial

Článok vyšiel v časopiseActa chirurgiae plasticae

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2022 Číslo 1- Metamizol jako analgetikum první volby: kdy, pro koho, jak a proč?

- Kombinace metamizol/paracetamol v léčbě pooperační bolesti u zákroků v rámci jednodenní chirurgie

- Kombinace paracetamolu s kodeinem snižuje pooperační bolest i potřebu záchranné medikace

- Metamizol v kostce a v praxi – účinné neopioidní analgetikum pro celé věkové spektrum

- Kombinace tramadol/paracetamol zmírňuje bolest v oblasti bederní páteře a může tak zmírnit i depresi

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Editorial

- Efficacy of pedicled anterolateral thigh flap for reconstruction of regional defects – a record analysis

- Depression and anxiety disorders in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome after surgery – a case control study

- Recurrence of breast ptosis after mastopexy – a prospective pilot study

- Development of a questionnaire for a patient-reported outcome after nasal reconstruction

- Breast reconstruction with autologous abdomen-based free flap with prior abdominal liposuction – a case-based review

- Superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap on extremity defects – case series

- Emergency evacuation low-pressure suction for the management of extravasation injuries – a case report

- Acta chirurgiae plasticae

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap on extremity defects – case series

- Efficacy of pedicled anterolateral thigh flap for reconstruction of regional defects – a record analysis

- Recurrence of breast ptosis after mastopexy – a prospective pilot study

- Breast reconstruction with autologous abdomen-based free flap with prior abdominal liposuction – a case-based review

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy